- an increased respiratory rate (tachypnea);

- changes in the normal heart rate (bradycardia or tachycardia);

- skin color change, such as turning blue around the lips, nose, and fingers/toes (cyanosis, mottled);

- temporary cessation of breathing (apnea);

- frequent stopping due to an uncoordinated suck–swallow–breathe pattern; and

- oxygen desaturation

Causes

Underlying etiologies associated with pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders include

- complex medical conditions (e.g., heart disease, pulmonary disease, allergies, gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], delayed gastric emptying);

- developmental disability;

- factors affecting neuromuscular coordination (e.g., prematurity, low birth weight, hypotonia, hypertonia);

- genetic syndromes;

- medication side effects (e.g., lethargy, decreased appetite);

- neurological disorders;

- sensory issues as a primary cause or secondary to limited food availability in early development (Beckett et al., 2002; Johnson & Dole, 1999);

- structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip and/or palate and other craniofacial abnormalities, laryngomalacia, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, choanal atresia, restrictive tethered oral tissues);

- behavioral factors; and

- socio-emotional factors.

Atypical eating and drinking behaviors can develop in association with dysphagia, aspiration, or a choking event. They may also arise in association with sensory disturbances (e.g., hypersensitivity to textures), stress reactions (e.g., consistent or repetitive gagging), traumatic events increasing anxiety, or undetected pain (e.g., teething, tonsillitis). See, for example, Manikam and Perman (2000).

Roles and Responsibilities

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a central role in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of infants and children with swallowing and feeding disorders. The professional roles and activities in speech-language pathology include clinical/educational services (diagnosis, assessment, planning, and treatment); prevention and advocacy; and education, administration, and research. See ASHA’s Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology (ASHA, 2016).

Appropriate roles for SLPs include

- educating families of children at risk for pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders;

- educating other professionals on the needs of children with feeding and swallowing disorders and the role of SLPs in diagnosis and management;

- conducting a comprehensive assessment, including clinical and instrumental evaluations as appropriate;

- considering culture as it pertains to food choices/habits, perception of disabilities, and beliefs about intervention (Davis-McFarland, 2008);

- diagnosing pediatric oral and pharyngeal swallowing disorders (dysphagia);

- recognizing signs of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and making appropriate referrals with collaborative treatment as needed;

- referring the patient to other professionals as needed to rule out other conditions, determine etiology, and facilitate patient access to comprehensive services;

- recommending a safe swallowing and feeding plan for the individualized family service plan (IFSP), individualized education program (IEP), or 504 plan;

- educating children and their families to prevent complications related to feeding and swallowing disorders;

- serving as an integral member of an interdisciplinary feeding and swallowing team;

- consulting and collaborating with other professionals, family members, caregivers, and others to facilitate program development and to provide supervision, evaluation, and/or expert testimony, as appropriate (see ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice [IPE/IPP] and person- and family-centered care);

- remaining informed of research in the area of pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders while helping to advance the knowledge base related to the nature and treatment of these disorders; and

- advocating for families and individuals with feeding and swallowing disorders at the local, state, and national levels.

Experience in adult swallowing disorders does not qualify an individual to provide swallowing assessment and intervention for children. Understanding adult anatomy and physiology of the swallow provides a basis for understanding dysphagia in children, but SLPs require knowledge and skills specific to pediatric populations. As indicated in the ASHA Code of Ethics (ASHA, 2023), SLPs who serve a pediatric population should be educated and appropriately trained to do so.

Dysphagia Teams

The causes and consequences of dysphagia cross traditional boundaries between professional disciplines. Therefore, management of dysphagia may require input of multiple specialists serving on an interprofessional team. Members of the dysphagia team may vary across settings.

The SLP frequently serves as coordinator for the team management of dysphagia. SLPs lead the team in

- identifying core team members and support services,

- training team members,

- facilitating communication between team members,

- tracking and documenting team activity,

- actively consulting with team members, and

- assisting in discharge planning.

School Setting Considerations

School-based SLPs play a significant role in the management of feeding and swallowing disorders. SLPs provide assessment and treatment to the student as well as education to parents, teachers, and other professionals who work with the student daily. SLPs develop and typically lead the school-based feeding and swallowing team.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA, 2004) protects the rights of students with disabilities, ensures free appropriate public education, and mandates services for students who may have health-related disorders that impact their ability to fully participate in the educational curriculum. Feeding, swallowing, and dysphagia are not specifically mentioned in IDEA; however, school districts must protect the health and safety of students with disabilities in the schools, including those with feeding and swallowing disorders. According to IDEA, students with disabilities may receive school health and nursing as related services to address safe mealtimes regardless of their special education classification.

Although feeding, swallowing, and dysphagia are not specifically mentioned in IDEA, the U.S. Department of Education acknowledges that chronic health conditions could deem a student eligible for special education and related services under the disability category “Other Health Impairment,” if the disorder interferes with the student’s strength, vitality, or alertness and limits the student’s ability to access the educational curriculum.

Students who do not qualify for IDEA services and have swallowing and feeding disorders may receive services through the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, under the provision that it substantially limits one or more of life’s major activities.

School districts that participate in the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service Program in the schools, known as the National School Lunch Program, must follow regulations [see 7 C.F.R. § 210.10(m)(1)] to provide substitutions or modifications in meals for children who are considered disabled and whose disabilities restrict their diet (Meal Requirements for Lunches and Requirements for Afterschool Snacks, 2021). [1]

[1] Here, we cite the most current, updated version of 7 C.F.R. § 210.10 (from 2021), in which the section letters and numbers are “210.10(m)(1).” The original version was codified in 2011—and has had many updates since. Those section letters and numbers from 2011 are “210.10(g)(1)” and can be found at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2011-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2011-title7-vol4-sec210-10.pdf.

Educational Relevance

IDEA protects the rights of students with disabilities and ensures free appropriate public education. Feeding and swallowing disorders may be considered educationally relevant and part of the school system’s responsibility to ensure

- safety while eating in school, including having access to appropriate personnel, food, and procedures to minimize risks of choking and aspiration while eating;

- adequate nourishment and hydration so that students can attend to and fully access the school curriculum;

- student health and well-being (e.g., free from aspiration pneumonia or other illnesses related to malnutrition or dehydration) to maximize their attendance and academic ability/achievement at school; and

- skill development for eating and drinking efficiently during meals and snack times so that students can complete these activities with their peers safely and in a timely manner.

Please see Clinical Evaluation: Schools section below for further details.

Assessment

See the Assessment section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

Assessment and treatment of swallowing and swallowing disorders may require the use of appropriate personal protective equipment and universal precautions.

Consistent with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework (ASHA, 2023; WHO, 2001), a comprehensive assessment is conducted to identify and describe

- impairments in body structure and function, including which swallowing phases are affected;

- comorbid deficits or conditions, such as developmental disabilities or syndromes;

- limitations in activity and participation, including the impact on overall health (including nutrition and hydration) and the child’s ability to participate in routine activities;

- contextual (environmental and personal) factors that serve as barriers to or facilitators of successful nutritional intake (e.g., child’s food preferences, family support in implementing strategies for safe eating and drinking); and

- quality of life of the child and family as it relates to feeding and swallowing impairments.

See Person-Centered Focus on Function: Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing [PDF] for examples of assessment data consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework.

Clinicians may consider the following factors when assessing feeding and swallowing disorders in the pediatric population:

- Congenital abnormalities and/or chronic conditions can affect feeding and swallowing function.

- Feeding skills of premature infants will be consistent with neurodevelopmental level rather than chronological age or adjusted age.

- Positioning limitations and abilities (e.g., children who use a wheelchair) may affect intake and respiration.

- Infants cannot verbally describe their symptoms, and children with reduced communication skills may not be able to adequately do so. Clinicians must rely on

- a thorough case history;

- parent interviews;

- weight gain and growth trajectory;

- data from monitoring devices (e.g., for patients in the neonatal intensive care unit [NICU]);

- nonverbal forms of communication (e.g., behavioral cues signaling feeding or swallowing problems); and

- observations of the caregiver’s behaviors and ability to read the child’s cues as they feed the child.

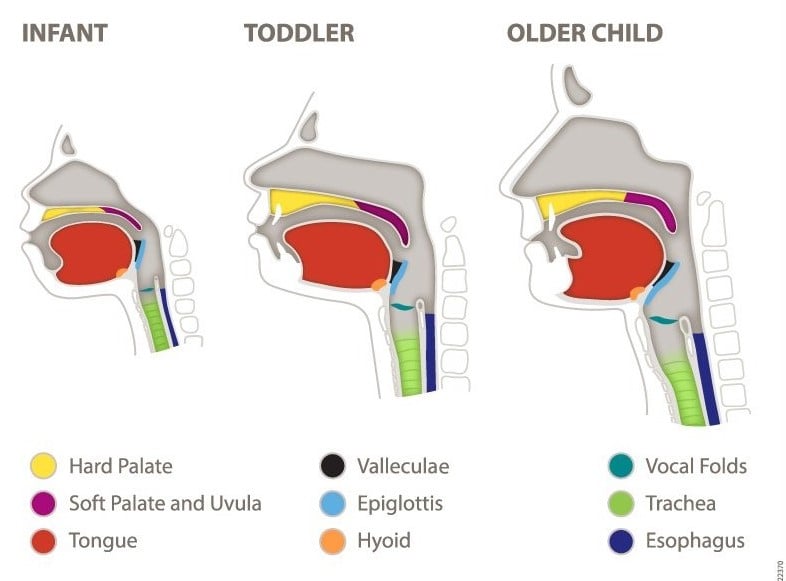

As infants and children grow and develop, the absolute and relative size and shape of oral and pharyngeal structures change. See figures below.

Lateral views of infant head, toddler head, and older child head showing structures involved in swallowing. From Arvedson, J.C., & Lefton-Greif, M.A. (1998). Pediatric Videofluroscopic Swallow Studies: A Professional Manual With Caregiver Guidelines. Copyright ©1998 Joan C. Arvedson. Reproduced and adapted with permission. All rights reserved.

Anatomical and physiological differences include the following:

- In infants, the tongue fills the oral cavity, and the velum hangs lower. The hyoid bone and the larynx are positioned higher than in adults, and the larynx elevates less than in adults during the pharyngeal phase of the swallow.

- Once the infant begins eating pureed food, each swallow is discrete (as opposed to sequential swallows in bottle-fed or breastfed/chestfed infants), and the oral and pharyngeal phases are similar to those of an adult (although with less elevation of the larynx).

- As the child matures, the intraoral space increases as the mandible grows down and forward, and the oral cavity elongates in the vertical dimension. The space between the tongue and the palate increases, and the larynx and the hyoid bone lower, elongating and enlarging the pharynx (Logemann, 1998).

Chewing matures as the child develops (see, e.g., Gisel, 1988; Le Révérend et al., 2014; Wilson & Green, 2009). Concurrent medical issues may affect this timeline. Foods given during the assessment should be consistent with the child’s current level of chewing skills.

Clinical Evaluation

A clinical evaluation of swallowing and feeding is the first step in determining the presence or absence of a swallowing disorder.

The evaluation may address

- eating,

- drinking,

- secretion management,

- oral hygiene,

- sensory status,

- the ability to accept food,

- the amount of diversity in their diet,

- management of oral medications, and

- the caregiver’s behaviors while feeding their child.

SLPs conduct assessments in a manner that is sensitive and responsive to the family’s cultural background, religious beliefs, dietary beliefs/practices/habits, history of disordered eating behaviors, and preferences for medical intervention. Families are encouraged to bring food and drink common to their household and utensils typically used by the child. Typical feeding practices and positioning should be used during assessment. Cultural, religious, and individual beliefs about food and eating practices may affect an individual’s comfort level or willingness to participate in the assessment. Some eating habits that appear to be a sign or symptom of a feeding disorder (e.g., avoiding certain foods or refusing to eat in front of others) may, in fact, be related to cultural differences in meal habits or may be symptoms of an eating disorder (National Eating Disorders Association, n.d.).

SLPs do not diagnose or treat eating disorders such as bulimia, anorexia, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; in the cases where these disorders are suspected, the SLP should refer to the appropriate behavioral health professional.

The clinical evaluation typically begins with a case history based on a comprehensive review of medical/clinical records and interviews with the family and health care professionals.

Prior to bolus delivery, the SLP may assess the following:

- overall physical, social, behavioral, and communicative development

- gross and fine motor development

- cranial nerve function

- structures of the face, jaw, lips, tongue, hard and soft palate, oral pharynx, and oral mucosa

- functional use of muscles and structures used in swallowing, including

- symmetry,

- sensation,

- strength,

- tone,

- range and rate of motion, and

- coordination of movement

- typically used utensils or

- utensils that the child may reject or find challenging

- suckling and sucking in infants,

- mastication in older children,

- oral containment,

- manipulation and transfer of the bolus, and

- the ability to eat within the time allotted at school

- an acceptance of the pacifier, nipple, spoon, and cup;

- the range and texture of developmentally appropriate foods and liquids tolerated; and

- the willingness to participate in mealtime experiences with caregivers

- medical or surgical specialists,

- a registered dietitian,

- a psychologist or social worker,

- an occupational therapist (OT),

- a physical therapist (PT), or

- a dentist

Team Approach

A team approach is necessary for appropriately diagnosing and managing pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders, as the severity and complexity of these disorders vary widely in this population (McComish et al., 2016). The SLP who specializes in feeding and swallowing disorders typically leads the professional care team in the clinical or educational setting.

In addition to the SLP, team members may include

- family and/or caregivers;

- a registered dietitian;

- a lactation consultant (infants);

- a nurse;

- an OT;

- a physician, such as

- a pediatrician,

- a neonatologist,

- an otolaryngologist,

- a gastroenterologist,

- a dentist, or

- a psychologist or psychiatrist;

Additional medical and rehabilitation specialists may be included, depending on the type of facility, the professional expertise needed, and the specific population being served.

Clinical Evaluation: Infants

The clinical evaluation for infants from birth to 1 year of age—including those in the NICU—includes an evaluation of prefeeding skills, an assessment of readiness for oral feeding, an evaluation of breastfeeding/chestfeeding and bottle-feeding ability, and observations of caregivers feeding the child.

SLPs should have extensive knowledge of

- embryology,

- prenatal and perinatal development,

- medical issues common to preterm and medically fragile newborns,

- typical early infant development,

- neuroprotection,

- neonatal care,

- respiratory support,

- medical comorbidities common in the NICU, and

- the role of providers in the NICU.

Appropriate referrals to medical professionals should be made when anatomical or physiological abnormalities are found during the clinical evaluation. The clinical evaluation of infants typically involves

- a case history, which includes

- gestational and birth history and

- pertinent medical history;

- a developmental assessment,

- a respiratory status assessment, and

- an assessment of sucking/swallowing problems and a determination of abnormal anatomy and/or physiology that might be associated with these findings (e.g., Francis et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2013);

Readiness for Oral Feeding

Protocols for determining readiness for oral feeding and specific criteria for initiating feeding vary across facilities. Feeding readiness in NICUs may be a unilateral decision on the part of the neonatologist or a collaborative process involving the SLP, neonatologist, and nursing staff.

Key criteria to determine readiness for oral feeding include

- physiologic stability—stability of digestive, respiratory, heart rate, and oxygenation parameters;

- motoric stability—stability of muscle tone, flexion, and midline movements; and

- behavioral state—including the ability to become alert to a stimulus and remain alert.

Decisions regarding the initiation of oral feeding are based on recommendations from the medical and therapeutic team, with input from the parent and caregivers.

Non-Nutritive Sucking (NNS)

NNS is sucking for comfort without fluid release (e.g., with a pacifier, finger, or recently emptied breast). NNS does not determine readiness to orally feed, but it is helpful for assessment. NNS patterns can typically be evaluated with skilled observation and without the use of instrumental assessment.

A non-instrumental assessment of NNS includes an evaluation of the following:

- The infant’s oral structures and functions, including palatal integrity, jaw movement, and tongue movements for cupping and compression. (Note: Lip closure is not required for infant feeding because the tongue typically seals the anterior opening of the oral cavity.)

- The infant’s ability to turn the head and open the mouth (rooting) when stimulated on the lips or cheeks and to accept a pacifier into the mouth.

- The infant’s ability to use both compression (positive pressure of the jaw and tongue on the pacifier) and suction (negative pressure created with tongue cupping and jaw movement).

- The infant’s compression and suction strength.

- The infant’s ability to maintain a stable physiological state (e.g., oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate) during NNS.

Nutritive Sucking (NS)

The clinician can determine the appropriateness of NS following an NNS assessment. Any loss of stability in physiologic, motoric, or behavioral state from baseline should be taken into consideration at the time of the assessment.

NS skills are assessed during breastfeeding/chestfeeding and bottle-feeding if both modes are going to be used. SLPs should be sensitive to family values, beliefs, and access regarding bottle-feeding and breastfeeding/chestfeeding and should consult with parents and collaborate with nurses, lactation consultants, and other medical professionals to help identify parent preferences.

Assessment of NS includes an evaluation of the following:

- sucking/swallowing/breathing pattern—ability to coordinate a suck/swallow/breathe pattern

- efficiency—volume of intake per minute

- endurance—ability to remain engaged in the feeding to finish the required volumes while sustaining appropriate feeding patterns

- the feeding relationship—interaction between the infant and the feeder

The infant’s communication behaviors during feeding can be used to guide a flexible assessment. These cues can communicate the infant’s ability to tolerate bolus size, the need for more postural support, and if swallowing and breathing are no longer synchronized. In turn, the caregiver can use these cues to optimize feeding by responding to the infant’s needs in a dynamic fashion at any given moment (Shaker, 2013b).

Breastfeeding/Lactation/Nursing

SLPs collaborate with parents, nurses, and lactation consultants prior to assessing feeding skills when appropriate. This requires a working knowledge of nursing strategies to facilitate safe and efficient swallowing.

In addition to the clinical evaluation of infants noted above, lactation assessment typically includes an evaluation of the

- infant’s general health;

- infant’s medical comorbidities;

- infant’s current state, including respiratory rate and heart rate;

- infant’s behavior (e.g., positive rooting, willingness to suckle);

- infant’s position (e.g., well supported, tucked against the caregiver’s body);

- infant’s ability to latch;

- efficiency and coordination of the infant’s suck/swallow/breathe pattern;

- health of the caregiver’s mammary tissue, if present; and

- parent’s behavior (e.g., comfort with lactation, confidence in handling the infant, awareness of the infant’s cues during feeding).

Bottle-Feeding

The assessment of bottle-feeding includes an evaluation of the

- infant’s general health;

- infant’s medical comorbidities;

- infant’s current state, including the respiratory rate and heart rate;

- infant’s behavior (willingness to accept nipple);

- caregiver’s behavior while feeding the infant;

- efficiency and coordination of the infant’s suck/swallow/breathe pattern;

- nipple type and form of nutrition (breast milk or formula);

- infant’s position;

- quantity of intake;

- length of time the infant takes for one feeding; and

- infant’s response to attempted interventions, such as

- a different nipple for flow control,

- external pacing,

- a different bottle to control air intake, and

- different positions (e.g., side feeding).

Spoon-Feeding

The assessment of spoon-feeding includes an evaluation of the optimal spoon type and the infant’s ability to

- move their head toward the spoon and then open their mouth,

- turn their head away from the spoon to show that they have had enough,

- close their lips around the spoon,

- clear food from the spoon with their top lip,

- move food from the spoon to the back of their mouth, and

- attempt to spoon-feed independently.

Clinical Evaluation: Toddlers and Preschool/School-Age Children

In addition to the areas of assessment noted above, the evaluation for toddlers (ages 1–3 years) and preschool/school-age children (ages 3–21 years) may include

- a review of any past diagnostic test results,

- a review of current programs and treatments,

- an assessment of current skills and limitations at home and in other day settings,

- screening of willingness to accept liquids and a variety of foods in multiple food groups to determine risk factors for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder,

- an evaluation of dependence on nutritional supplements to meet dietary needs,

- an evaluation of independence and the need for supervision and assistance, and

- the use of intervention probes to identify strategies that might improve function.

Clinical Evaluation: Schools

Evaluation in the school setting includes children/adults from 3 to 21 years of age. The school-based SLP and the school team (OT, PT, and school nurse) conduct the evaluation, which includes observation of the student eating a typical meal or snack. Implementation of strategies and modifications is part of the diagnostic process. Additional components of the evaluation include

- parent interviews and a case history;

- an assessment of oral structures and function during intake;

- an assessment to determine the developmental level of feeding skills;

- an assessment of issues related to fatigue and access to nutrition and hydration during school;

- a determination of duration of mealtime experiences, including the ability to eat within the school’s mealtime schedule;

- an assessment of response to intake, including the ability to manipulate and propel the bolus, coughing, choking, or pocketing foods;

- an assessment of adaptive equipment for eating and positioning by an OT and a PT; and

- an assessment of behaviors that relate to the child’s response to food.

Referral

The evaluation process begins with a referral to a team of professionals within the school district who are trained in the identification and treatment of feeding and swallowing disorders. The referral can be initiated by families/caregivers or school personnel.

The process of identifying the feeding and swallowing needs of students includes a review of the referral, interviews with the family/caregiver and teacher, and an observation of students during snack time or mealtime. A physician’s order to evaluate is typically not required in the school setting; however, it is best practice to collaborate with the student’s physician, particularly if the student is medically fragile or under the care of a physician.

The school SLP (or case manager) contacts the family to obtain consent for an evaluation if further evaluation is deemed necessary. They also discuss the evaluation process and gather information about the child’s medical and health history as well as their eating habits and typical diet at home.

Parental Interview/Case History

The school SLP (or case manager) contacts the family to notify them of the school team’s concerns. At that time, they

- discuss the process of establishing a safe feeding plan for the student at school;

- gather information about the student’s medical, health, feeding, and swallowing history;

- identify the current mealtime habits and diet at home; and

- identify any parental or student concerns or stress regarding mealtimes.

Team Approach

The school-based feeding and swallowing team consists of parents and professionals within the school as well as professionals outside the school (e.g., physicians, dietitians, and psychologists). Members of the team include, but are not limited to, the following:

- SLP

- family/caregiver

- classroom teacher and assistant

- school nurse

- OT

- PT

- school administrator

- behavioral specialist

- school psychologist

- social worker

- dietitian

- cafeteria staff

The team works together to

- inform all members of the process for identifying and treating feeding and swallowing disorders in the schools, including the roles and responsibilities of team members;

- contribute to the development and implementation of the feeding and swallowing plan as well as documentation on the individualized education program and the individualized health plan; and

- oversee the day-to-day implementation of the feeding and swallowing plan and any individualized education program strategies to keep the student safe from aspiration, choking, undernutrition, or dehydration while in school.

If the school team determines that a medical assessment, such as a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), sometimes also called fiber-optic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing, or other medical assessment, is required during the student’s program, the team works with the family to seek medical consultation or referral. A written referral or order from the treating physician is required for instrumental evaluations such as VFSS or FEES.

Collaboration With Outside Medical Professionals

Best practice indicates establishing open lines of communication with the student’s physician or other health care provider—either through the family or directly—with the family’s permission. Any communication by the school team to an outside physician, facility, or individual requires signed parental consent.

In the school setting a physician’s order or prescription is not required to perform clinical evaluations, modify diets, or to provide intervention. However, there are times when a prescription, referral, or medical clearance from the student’s primary care physician or other health care provider is indicated, such as when the student

- receives part or all of their nutrition or hydration via enteral or parenteral tube feeding,

- has a complex medical condition and experiences a significant change in status,

- has recently been hospitalized with aspiration pneumonia,

- has had a recent choking incident and has required emergency care,

- is suspected of having aspirated food or liquid into the lungs, and/or

- has suspected structural abnormalities (requires an assessment from a medical professional).

See ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP) and collaboration and teaming for guidance on successful collaborative service delivery across settings.

See the treatment in the school setting section below for further information.

Instrumental Evaluation

Instrumental evaluation is conducted following a clinical evaluation when further information is needed to determine the nature of the swallowing disorder. Instrumental assessments can help provide specific information about anatomy and physiology otherwise not accessible by noninstrumental evaluation. Instrumental evaluation can also help determine if swallow safety can be improved by modifying food textures, liquid consistencies, and positioning or implementing strategies.

Instrumental evaluation is completed in a medical setting. These studies are a team effort and may include the radiologist, radiology technician, and SLP. The SLP or radiology technician typically prepares and presents the barium items, whereas the radiologist records the swallow for visualization and analysis. Please see AHSA’s resource on state instrumental assessment requirements for further details.

The two most commonly used instrumental evaluations of swallowing for the pediatric population are

- videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) and

- flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES)

During an instrumental assessment of swallowing, the clinician may use information from cardiac, respiratory, and oxygen saturation monitors to monitor any changes to the physiologic or behavioral condition. Other signs to monitor include color changes, nasal flaring, and suck/swallow/breathe patterns.

The roles of the SLP in the instrumental evaluation of swallowing and feeding disorders include

- participating in decisions regarding the appropriateness of these procedures;

- conducting the VFSS and FEES instrumental procedures;

- interpreting and applying data from instrumental evaluations to

- determine the severity and nature of the swallowing disorder and the child’s potential for safe oral feeding; and

- formulate feeding and swallowing treatment plans, including recommendations for optimal feeding techniques;

- manofluorography,

- cervical auscultation,

- scintigraphy (which, in the pediatric population, may also be referred to as “radionuclide milk scanning”),

- pharyngeal manometry,

- 24-hour pH monitoring, and

- esophagoscopy.

General Considerations for Instrumental Evaluations

Determining the appropriate procedure to use depends on what needs to be visualized and which procedure will be best tolerated by the child. Prior to the instrumental evaluation, clinicians are encouraged to collaborate with the medical team regarding feeding schedules that will maximize feeding readiness during the evaluation.

The VFSS may be appropriate for a child who is currently NPO or has never eaten by mouth to determine whether the child has a functional swallow and which types of food they can manage. The decision to use a VFSS is made with consideration for the child’s responsiveness (e.g., acceptance of oral stimulation or tastes on the lips without signs of distress) and the potential for medical complications. Careful pulmonary monitoring during a modified barium swallow is essential to help determine the child’s endurance over a typical mealtime.

When conducting an instrumental evaluation, SLPs should consider the following:

- Anxiety and crying may be expected reactions to any instrumental procedure. Anxiety may be reduced by using distractions (e.g., videos), allowing the child to sit on the parent’s or the caregiver’s lap (for FEES procedures), and decreasing the number of observers in the room.

- Positioning for the VFSS depends on the size of the child and their medical condition (Arvedson & Lefton-Greif, 1998; Geyer et al., 1995). Infants under 6 months of age typically require head, neck, and trunk support.

- Infants are obligate nasal breathers, and compromised breathing may result from the placement of a flexible endoscope in one nostril when a nasogastric tube is in place in the other nostril. Clinicians should discuss this with the medical team to determine options, including the temporary removal of the feeding tube and/or use of another means of swallowing assessment.

- Children are positioned as they are typically fed at home and in a manner that avoids spontaneous or reflex movements that could interfere with the safety of the examination. Modifications to positioning are made as needed and are documented as part of the assessment findings.

- If a natural feeding process (e.g., position, caregiver involvement, and use of familiar foods) cannot be achieved, the results may not represent typical swallow function, and the study may need to be terminated, with results interpreted with caution.

Test Environment

Procedures take place in a child-friendly environment with toys, visual distracters, rewards, and a familiar caregiver, if possible and when appropriate. Various items are available in the room to facilitate success and replicate a typical mealtime experience, including preferred foods, familiar food containers, utensil options, and seating options.

Preparing the Child

- For the child who is able to understand, the clinician explains the procedure, the purpose of the procedure, and the test environment in a developmentally appropriate manner.

- The clinician allows time for the child to get used to the room, the equipment, and the professionals who will be present for the procedure.

- For procedures that involve presentation of a solid and/or liquid bolus, the clinician instructs the family to schedule meals and snacks so that the child will be hungry and more likely to accept foods as needed for the study.

If the child is NPO, the clinician allows time for the child to develop the ability to accept and swallow a bolus. For children who have difficulty participating in the procedure, the clinician should allow time to control problem behaviors prior to initiating the instrumental procedure.

Preparing Families

- The clinician provides families and caregivers with information about dysphagia, the purpose for the study, the test procedures, and the test environment.

- The clinician requests that the family provide

- familiar foods of varying consistencies and tastes that are compatible with contrast material (if the facility protocol allows);

- a specialized seating system from home (including car seat or specialized wheelchair), as warranted and if permitted by the facility; and

- the child’s familiar and preferred utensils, if appropriate.

Treatment

See the Treatment section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

The primary goals of feeding and swallowing intervention for children are to

- support safe and adequate nutrition and hydration;

- determine the optimum feeding methods and techniques to maximize swallowing safety and feeding efficiency;

- collaborate with family to incorporate dietary preferences;

- attain age-appropriate eating skills in the most normal setting and manner possible (i.e., eating meals with peers in the preschool, mealtime with the family);

- minimize the risk of pulmonary complications;

- maximize the quality of life; and

- prevent future feeding issues with positive feeding-related experiences to the extent possible, given the child’s medical situation.

Consistent with the WHO’s (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework, goals are designed to

- facilitate the individual’s activities and participation by promoting safe, efficient feeding;

- capitalize on strengths and address weaknesses related to underlying structures and functions that affect feeding and swallowing;

- modify contextual factors that serve as barriers and enhance those that facilitate successful feeding and swallowing, including the development and use of appropriate feeding methods and techniques; and

- promote a meaningful and functional mealtime experience for children and families.

Medical, surgical, and nutritional factors are important considerations in treatment planning. Underlying disease state(s), chronological and developmental age of the child, social and environmental factors, and psychological and behavioral factors also affect treatment recommendations.

For children with complex feeding problems, an interdisciplinary team approach is essential for individualized treatment (McComish et al., 2016). See ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP), and collaboration and teaming.

Questions to ask when developing an appropriate treatment plan within the ICF framework include the following.

Can the child eat and drink safely?

Consider the child’s pulmonary status, nutritional status, overall medical condition, mobility, swallowing abilities, and cognition, in addition to the child’s swallowing function and how these factors affect feeding efficiency and safety.

Can the child receive adequate nutrition and hydration by mouth alone, given length of time to eat, efficiency, and fatigue factors?

This question is answered by the child’s medical team. If the child cannot meet nutritional needs by mouth, what recommendations need to be made concerning supplemental non-oral intake and/or the inclusion of orally fed supplements in the child’s diet ? The team may consider the tube-feeding schedule, type of pump, rate, calories, and so forth.

How can the child’s functional abilities be maximized?

This might involve decisions about whether the individual can safely eat an oral diet that meets nutritional needs, whether that diet needs to be modified in any way, and whether the individual needs compensatory strategies to eat the diet. Does the child have the potential to improve swallowing function with direct treatment?

How can the child’s quality of life be preserved and/or enhanced?

Consider how long it takes to eat a meal, fear of eating, pleasure obtained from eating, social interactions while eating, and so on (Huckabee & Pelletier, 1999). The family’s customs and traditions around mealtimes and food should be respected and explored.

Are there behavioral and sensory motor issues that interfere with feeding and swallowing?

Do these behaviors result in family/caregiver frustration or increased conflict during meals? Is a sensory motor–based intervention for behavioral issues indicated?

Treatment Considerations

The health and well-being of the child is the primary concern in treating pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. Families may have strong beliefs about the medicinal value of some foods or liquids. Such beliefs and holistic healing practices may not be consistent with recommendations made. If certain practices are contraindicated, the clinician can work with the family to determine alternatives that allow the child to safely participate as fully as possible.

Treatment selection will depend on the child’s age, cognitive and physical abilities, and specific swallowing and feeding problems. Keep in mind that infants and young children with feeding and swallowing disorders, as well as some older children with concomitant intellectual disabilities, often need intervention techniques that do not require them to follow simple verbal or nonverbal instructions. In these cases, intervention might consist of changes in the environment or indirect treatment approaches for improving safety and efficiency of feeding.

Treatment Options

Postural and Positioning Techniques

Postural and positioning techniques involve adjusting the child’s posture or position to establish central alignment and stability for safe feeding. These techniques serve to protect the airway and offer safer transit of food and liquid. No single posture will provide improvement to all individuals. Postural changes differ between infants and older children.

- chin down—tucking the chin down toward the neck;

- chin up—slightly tilting the head up;

- head rotation—turning the head to the weak side to protect the airway;

- upright positioning—90° angle at hips and knees, feet on the floor, with supports as needed;

- head stabilization—supported so as to present in a chin-neutral position;

- cheek and jaw assist;

- reclining position—using pillow support or a reclined infant seat with trunk and head support; and

- side-lying positioning (for infants).

Diet Modifications

Diet modifications consist of altering the viscosity, texture, temperature, portion size, or taste of a food or liquid to facilitate safety and ease of swallowing. Typical modifications may include thickening thin liquids, softening, cutting/chopping, or pureeing solid foods. Taste or temperature of a food may be altered to provide additional sensory input for swallowing. See International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI).

Diet modifications incorporate individual and family preferences, to the extent feasible. Consult with families regarding safety of medical treatments, such as swallowing medication in liquid or pill form, which may be contraindicated by the disorder. Diet modifications should consider the nutritional needs of the child to avoid undernutrition and malnutrition.

Precautions

Consumers should use caution regarding the use of commercial, gum-based thickeners for infants of any age (Beal et al., 2012; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017). Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) should be aware of these precautions and consult, as appropriate, with their facility to develop guidelines for using thickened liquids with infants.

Equipment and Utensils

Adaptive equipment and utensils may be used with children who have feeding problems to foster independence with eating and increase swallow safety by controlling bolus size or achieving the optimal flow rate of liquids.

Examples of adaptive equipment include

- modified nipples,

- cut-out cups,

- weighted forks and spoons,

- angled forks and spoons,

- sectioned plates,

- non-tip bowls, and

- Dycem® to prevent plates and cups from sliding.

SLPs work with oral and pharyngeal implications of adaptive equipment. SLPs may collaborate with occupational therapists, considering that motor control for the use of this adaptive equipment is critical.

Maneuvers/Exercises

Maneuvers are strategies used to change the timing or strength of movements of swallowing (Logemann, 2000). Some maneuvers require following multistep directions and may not be appropriate for young children and/or older children with cognitive impairments. Please see the Treatment section of ASHA’s Practice Portal page on Adult Dysphagia for further information. Examples of maneuvers include the following:

- Effortful swallow—Posterior tongue base movement is increased to facilitate bolus clearance.

- Mendelsohn maneuver—Elevation of the larynx is voluntarily prolonged at the peak of the swallow to help the bolus pass more efficiently through the pharynx and to prevent food/liquid from falling into the airway.

- Supraglottic swallow—Vocal folds are closed by voluntarily holding one’s breath before and during the swallow in order to protect the airway.

- Super-supraglottic swallow—An effortful breath hold tilts the arytenoid forward, which closes the airway entrance before and during the swallow.

Although sometimes referred to as the Masako maneuver, the Masako (or tongue-hold) is considered an exercise, not a maneuver. In the Masako, the tongue is held forward between the teeth while swallowing; this is performed without food or liquid in the mouth to prevent coughing or choking.

Postural/Position Techniques

Postural/position techniques redirect the movement of the bolus in the oral cavity and pharynx and modify pharyngeal dimensions. These techniques may be used prior to or during the swallow. Examples include the following:

- Chin-down posture—The chin is tucked down toward the neck to contain and control the bolus prior to initiating the swallow to potentially reduce penetration/aspiration.

- Chin-up posture—The chin is tilted up to facilitate bolus movement to the pharynx.

- Head rotation—The head is turned to either the left or the right side to direct the bolus toward the stronger side.

- Head tilt—The head is tilted toward the stronger side to keep the food on the chewing surface.

Please see the Treatment section of ASHA’s Practice Portal page on Adult Dysphagia for further information.

Oral–Motor Treatments

Oral–motor treatments include stimulation to—or actions of—the lips, jaw, tongue, soft palate, pharynx, larynx, and respiratory muscles. Oral–motor treatments range from passive (e.g., tapping, stroking, and vibration) to active (e.g., range-of-motion activities, resistance exercises, or chewing and swallowing exercises). Oral–motor treatments are intended to influence the physiologic underpinnings of the oropharyngeal mechanism to improve its functions. Some of these interventions can also incorporate sensory stimulation. Please visit ASHA’s Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for further information.

Feeding Strategies

Pacing—moderating the rate of intake by controlling or titrating the rate of presentation of food or liquid and the time between bites or swallows. Feeding strategies for children may include alternating bites of food with sips of liquid or swallowing 2–3 times per bite or sip. For infants, pacing can be accomplished by limiting the number of consecutive sucks. Strategies that slow the feeding rate may allow for more time between swallows to clear the bolus and may support more timely breaths.

Cue-based feeding—relies on cues from the infant, such as lack of active sucking, passivity, pushing the nipple away, or a weak suck. These cues typically indicate that the infant is disengaging from feeding and communicating the need to stop. They also provide information about the infant’s physiologic stability, which underlies the coordination of breathing and swallowing, and they guide the caregiver to intervene to support safe feeding. When the quality of feeding takes priority over the quantity ingested, the infant can set the pace of feeding and have more opportunity to enjoy the experience of feeding. As a result, intake is improved (Shaker, 2013a).

Rather than setting a goal to empty the bottle, the feeding experience is viewed as a partnership with the infant. The SLP plays a critical role in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), supporting and educating parents and other caregivers to understand and respond accordingly to the infant’s communication during feeding. Most NICUs have begun to move away from volume-driven feeding to cue-based feeding (Shaker, 2013a).

Responsive feeding—Like cue-based feeding, responsive feeding focuses on the caregiver-and-child dynamic. Responsive feeders attempt to understand and read a child’s cues for both hunger and satiety and respect those communication signals in infants, toddlers, and older children. Responsive feeding emphasizes communication rather than volume and may be used with infants, toddlers, and older children, unlike cue-based feeding that focuses on infants.

Sensory Stimulation Techniques

Sensory stimulation techniques vary and may include thermal–tactile stimulation (e.g., using an iced lemon glycerin swab) or tactile stimulation (e.g., using a NUK ™ brush) applied to the tongue or around the mouth. Children who demonstrate aversive responses to stimulation may need approaches that reduce the level of sensory input initially, with incremental increases as the child demonstrates tolerance. Sensory stimulation may be needed for children with reduced responses, overactive responses, or limited opportunities for sensory experiences.

Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral interventions are based on principles of behavioral modification and focus on increasing appropriate actions or behaviors—including increasing compliance—and reducing maladaptive behaviors related to feeding. Behavioral interventions include such techniques as antecedent manipulation, shaping, prompting, modeling, stimulus fading, and differential reinforcement of alternate behavior, as well as implementation of basic mealtime principles (e.g., scheduled mealtimes in a neutral atmosphere with no food rewards).

Biofeedback

Biofeedback includes instrumental methods (e.g., surface electromyography, ultrasound, nasendoscopy) that provide visual feedback during feeding and swallowing. Children with sufficient cognitive skills can be taught to interpret this visual information and make physiological changes during the swallowing process.

Electrical Stimulation

Electrical stimulation uses an electrical current to stimulate the peripheral nerve. SLPs with appropriate training and competence in performing electrical stimulation may provide the intervention. ASHA does not require any additional certifications to perform E-stim and urges members to follow the ASHA Code of Ethics, Principle II, Rule A which states: "Individuals who hold the Certificate of Clinical Competence shall engage in only those aspects of the professions that are within the scope of their professional practice and competence, considering their certification status, education, training, and experience" (ASHA, 2023).

If choosing to use electrical stimulation in the pediatric population, the primary focus should be on careful patient selection to ensure that electrical stimulation is being used only in situations where there is no possibility of inducing untoward effects. ASHA is strongly committed to evidence-based practice and urges members to consider the best available evidence before utilizing any product or technique. ASHA does not endorse any products, procedures, or programs, and therefore does not have an official position on the use of electrical stimulation or specific workshops or products associated with electrical stimulation.

Intraoral Prosthetics and Appliances

Intraoral prosthetics (e.g., palatal obturator, palatal lift prosthesis) can be used to normalize the intraoral cavity by providing compensation or physical support for children with congenital abnormalities (e.g., cleft palate) or damage to the oropharyngeal mechanism. With this support, swallowing efficiency and function may be improved.

Intraoral appliances (e.g., palatal plates) are removable devices with small knobs that provide tactile stimulation inside the mouth to encourage lip closure and appropriate lip and tongue position for improved functional feeding skills. Intraoral appliances are not commonly used.

Referrals may be made to dental professionals for assessment and fitting of these devices.

Tube Feeding

Tube feeding includes alternative avenues of intake such as via a nasogastric tube, a transpyloric tube (placed in the duodenum or jejunum), or a gastrostomy tube (a gastronomy tube placed in the stomach or a gastronomy–jejunostomy tube placed in the jejunum). Alternative feeding does not preclude the need for feeding-related treatment. These approaches may be considered by the medical team if the child’s swallowing safety and efficiency cannot reach a level of adequate function or does not adequately support nutrition and hydration. In these instances, the swallowing and feeding team will

- consider the optimum tube-feeding method that best meets the child’s needs and

- determine whether the child will need tube feeding for a short or an extended period of time.

Please see ASHA’s resource on alternative nutrition and hydration in dysphagia care for further information.

Treatment in the NICU and Infant Care Units

Clinicians working in the NICU should be aware of the multidisciplinary nature of this practice area, the variables that influence infant feeding, and the process for developing appropriate treatment plans in this setting. The NICU is considered an advanced practice area, and inexperienced SLPs should be aware that additional training and competencies may be necessary.

In all cases, the SLP must have an accurate understanding of the physiologic mechanism behind the feeding problems seen in this population. This understanding gives the SLP the necessary knowledge to choose appropriate treatment interventions and provide rationale for their use in the NICU.

Communication

In their role as communication specialists, SLPs monitor the infant for stress cues and teach parents and other caregivers to recognize and interpret the infant’s communication signals. SLPs treating preterm and medically fragile infants must be well versed in typical infant behavior and development so that they can recognize and interpret changes in behavior. These changes can provide cues that signal well-being or stress during feeding.

Behaviors can include changes in the following:

- autonomic system—pattern of respiration (pauses, tachypnea), color changes (red, pale, dusky, mottled), and visceral signs (e.g., spit-up, gag, burp)

- movement—postural alignment (hyperflexed, extended); muscle tone (flaccid, hypertonicity); movement patterns in the extremities, trunk, head, and face; and level of motor activity

- state—the range of available states of consciousness (i.e., deep sleep, quiet alert, and crying), the smoothness of transition between them, and the clarity of their expression

- attention—the infant’s ability to orient and focus on environmental stimuli, such as faces, sounds, or objects

Readiness for Oral Feeding

Readiness for oral feeding in the preterm or acutely ill, full-term infant is associated with

- the infant’s ability to come into and maintain awake states and to coordinate breathing with sucking and swallowing (McCain, 1997) as well as

- the presence or absence of apnea. Apnea is strongly correlated with longer transition time to full oral feeding (Mandich et al., 1996).

Supportive interventions to facilitate early feeding and/or to promote readiness for feeding include kangaroo mother care (KMC), non-nutritive sucking (NNS), oral administration of maternal milk, feeding protocols, and positioning (e.g., swaddling).

It is important to consult with the physician to determine when to begin oral feeding for children who have been NPO for an extended time frame. It is also important to consider any behavioral and/or sensory components that may influence feeding when exploring the option to begin oral feeding.

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC)

KMC—skin-to-skin contact between a caregiver and their newborn infant—can be an important factor in helping the infant achieve readiness for oral feeding, particularly breastfeeding/chestfeeding. Other benefits of KMC include temperature regulation, promotion of breastfeeding/chestfeeding, parental empowerment and bonding, stimulation of lactation, and oral stimulation for the promotion of oral feeding ability.

Non-Nutritive Sucking (NNS) Facilitation

NNS involves allowing an infant to suck without taking milk, either at the breast/chest (after milk has been expressed) or with the use of a pacifier. It is used as a treatment option to encourage eventual oral intake. The SLP providing and facilitating oral experiences with NNS must take great care to ensure that the experiences are positive and do not elicit stress or other negative consequences. The SLP also teaches parents and other caregivers to provide positive oral experiences and to recognize and interpret the infant’s cues during NNS.

Oral Administration of Maternal Milk

Administration of small amounts of maternal milk into the oral cavity of enteral tube–dependent infants improves breastfeeding rates, growth, and immune-protective factors and reduces sepsis (Pados & Fuller, 2020). It may also improve the timing of oral feeding initiation (Simpson et al., 2002), increase rates of “majority breastmilk” enteral feeds compared to those who receive tube feeding of formula alone (Snyder et al., 2017), and allow for earlier attainment of full enteral feedings (Rodriguez & Caplan, 2015).

Feeding Protocols

Feeding protocols include those that consider infant cues (i.e., responsive feeding) and those that are based on a schedule (i.e., scheduled feeding).

The following factors are considered prior to initiating and systematically advancing oral feeding protocols:

- alertness

- demand for feeding

- infant cues that signal stress

- neurodevelopmental level

- general health status

Treatment for Toddlers and Older Children

The management of feeding and swallowing disorders in toddlers and older children may require a multidisciplinary approach—especially for children with complex medical conditions.

Similar to treatment for infants in the NICU, treatment for toddlers and older children takes a number of factors into consideration, including the following:

- Readiness for oral feeding—Toddlers and older children who are beginning to eat orally for the first time or after an extended period of non-oral feeding will need time to become comfortable in the presence of food and to explore food without experiencing physiological responses (e.g., for children with significant gastrointestinal problems).

- Communication—SLPs can help caregivers understand emerging vocabulary related to food (e.g., names of foods and various flavors) as well as how children might be using feeding behaviors (e.g., food refusal responses) to communicate.

- Physical conditions—Treatment for children with conditions and disorders that affect movement (e.g., cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy) will need to take into consideration length of time to fatigue, optimal feeding methods, and positioning to maximize safe feeding and swallowing.

Treatment in the School Setting

Management of students with feeding and swallowing disorders in the schools addresses the impact of the disorder on the student’s educational performance and promotes the student’s safe swallow in order to avoid choking and/or aspiration pneumonia. Students with recurrent pneumonia may miss numerous school days, which has a direct impact on their ability to access the educational curriculum.

Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Information from the referral, parent interview/case history, and clinical evaluation of the student is used to develop IEP goals and objectives for improved feeding and swallowing, if appropriate.

Feeding and Swallowing Plan

A feeding and swallowing plan addresses diet and environmental modifications and procedures to minimize aspiration risk and optimize nutrition and hydration. Ongoing staff and family education is essential to student safety. The plan should be reviewed annually along with the IEP goals and objectives or as needed if significant changes occur or if it is found to be ineffective.

A feeding and swallowing plan may include but not be limited to

- student demographic information;

- appropriate positioning of the student for a safe swallow;

- specialized equipment indicated for positioning, as needed;

- environmental modifications to minimize distractions;

- adapted utensils for mealtimes (e.g., low flow cup, curved spoon/fork);

- recommended diet consistency, including food and liquid preparation/modification;

- sensory modifications, including temperature, taste, or texture;

- food presentation techniques, including wait time and amount;

- the level of assistance required for eating and drinking; and/or

- cues or prompts for eating and drinking.

Individualized Health Plan/Individualized Health Care Plan

An individualized health plan or individualized health care plan may be developed as part of the IEP or 504 plan to establish appropriate health care that may be needed for students with feeding and/or swallowing disorder. The plan includes a protocol for response in the event of a student health emergency (Homer, 2008). Staff who work closely with the student should have training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the Heimlich maneuver.

Transitioning Adolescents and Adults

Feeding and swallowing challenges can persist well into adolescence and adulthood. Precautions, accommodations, and adaptations must be considered and implemented as students transition to postsecondary settings. See ASHA’s resource on Postsecondary Transition Planning for information about transition planning.

Periodic assessment and monitoring of significant changes are necessary to ensure ongoing swallow safety and adequate nutrition throughout adulthood. A risk assessment for choking and an assessment of nutritional status should be considered part of a routine examination for adults with disabilities, particularly those with a history of feeding and swallowing problems. See, for example, Moreno-Villares (2014) and Thacker et al. (2008).

Service Delivery

See the Service Delivery section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

In addition to determining the type of treatment that is optimal for the child with feeding and swallowing problems, SLPs consider other service delivery variables that may affect treatment outcomes, including format, provider, dosage, and setting. Decisions are made based on the child’s needs, their family’s views and preferences, and the setting where services are provided.

Format

Format refers to the structure of the treatment session (e.g., group and/or individual). The appropriateness of the treatment format often depends on the child’s age, the type and severity of the feeding or swallowing problem, and the service delivery setting.

Provider

Provider refers to the person providing treatment (e.g., SLP, occupational therapist, or other feeding specialist). Recommended practices follow a collaborative process that involves an interdisciplinary team, including the child, family, caregivers, and other related professionals. When treatment incorporates accommodations, modifications, and supports in everyday settings, SLPs often provide training and education in how to use strategies to facilitate safe swallowing.

Dosage

Dosage refers to the frequency, intensity, and duration of service. Dosage depends on individual factors, including the child’s medical status, nutritional needs, and readiness for oral intake.

Setting

Setting refers to the location of treatment and varies across the continuum of care (e.g., NICU, intensive care unit, inpatient acute care, outpatient clinic, home, or school).

Resources

ASHA Resources

- Aerosol Generating Procedures

- Dysphagia Management for School Children: Dealing With Ethical Dilemmas

- Feeding and Swallowing Disorders in Children [Consumer Information]

- Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES)

- Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Practice (IPE/IPP)

- Medicaid Reimbursement in Schools

- Palliative and End-of-Life Care

- Pediatric Feeding Assessments and Interventions [Webinar]

- Person- and Family-Centered Care

- Pick the Right Code for Pediatric Dysphagia

- Postsecondary Transition Planning

- State Instrumental Assessment Requirements

- Swallowing and Feeding Team Referral Plan (Sample Form) [PDF]

- The Value of the Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) in Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Disorders (FSDs) [PDF]

- Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS)

Other Resources

This list of resources is not exhaustive, and the inclusion of any specific resource does not imply endorsement from ASHA.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement—Prevention of Choking Among Children [PDF]

- Community management of uncomplicated acute malnutrition in infants < 6 months of age (C-MAMI) [PDF]

- Developmental Stages in Infant and Toddler Feeding [PDF]

- Feeding Matters

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP)

- International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI)

- La Leche League International

- Management of Swallowing and Feeding Disorders in Schools

- National Foundation of Swallowing Disorders

- Pediatric Feeding Association

- RadiologyInfo.org: Video Fluoroscopic Swallowing Exam (VFSE)

- RCSLT: New Long COVID Guidance and Patient Handbook

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2016). Feeding and eating disorders: DSM-5 Selections.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Scope of practice in speech-language pathology [Scope of practice]. https://www.asha.org/policy/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2023). Code of ethics [Ethics]. https://www.asha.org/policy/

Arvedson, J. C. (2008). Assessment of pediatric dysphagia and feeding disorders: Clinical and instrumental approaches. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 14(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/ddrr.17

Arvedson, J. C., & Brodsky, L. (2002). Pediatric swallowing and feeding: Assessment and management. Singular.

Arvedson, J. C., & Lefton-Greif, M. A. (1998). Pediatric videofluoroscopic swallow studies: A professional manual with caregiver guidelines. Communication Skill Builders.

Beal, J., Silverman, B., Bellant, J., Young, T. E., & Klontz, K. (2012). Late onset necrotizing enterocolitis in infants following use of a xanthan gum-containing thickening agent. The Journal of Pediatrics, 161(2), 354–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.054

Beckett, C., Bredenkamp, D., Castle, J., Groothues, C., O’Connor, T. G., Rutter, M., & the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. (2002). Behavior patterns associated with institutional deprivation: A study of children adopted from Romania. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 23(5), 297–303.

Benfer, K. A., Weir, K. A., Bell, K. L., Ware, R. S., Davies, P. S. W., & Boyd, R. N. (2014). Oropharyngeal dysphagia in preschool children with cerebral palsy: Oral phase impairments. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(12), 3469–3481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.08.029

Benfer, K. A., Weir, K. A., Bell, K. L., Ware, R. S., Davies, P. S. W., & Boyd, R. N. (2017). Oropharyngeal dysphagia and cerebral palsy. Pediatrics, 140(6), e20170731. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0731

Bhattacharyya, N. (2015). The prevalence of pediatric voice and swallowing problems in the United States. The Laryngoscope, 125(3), 746–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24931

Black, L. I., Vahratian, A., & Hoffman, H. J. (2015). Communication disorders and use of intervention services among children aged 3–17 years: United States, 2012 [NCHS Data Brief No. 205]. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db205.htm

Brackett, K., Arvedson, J. C., & Manno, C. J. (2006). Pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders: General assessment and intervention. SIG 13 Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia), 15(3), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1044/sasd15.3.10

Calis, E. A. C., Veuglers, R., Sheppard, J. J., Tibboel, D., Evenhuis, H. M., & Penning, C. (2008). Dysphagia in children with severe generalized cerebral palsy and intellectual disability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 50(8), 625–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03047.x

Caron, C. J. J. M., Pluijmers, B. I., Joosten, K. F. M., Mathijssen, I. M. J., van der Schroeff, M. P., Dunaway, D. J., Wolvius, E. B., & Koudstaal, M. J. (2015). Feeding difficulties in craniofacial microsomia: A systematic review. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, 44(6), 732–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2015.02.014

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm

Davis-McFarland, E. (2008). Family and cultural issues in a school swallowing and feeding program. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2008/020)

de Vries, I. A. C., Breugem, C. C., van der Heul, A. M. B., Eijkemans, M. J. C., Kon, M., & Mink van der Molen, A. B. (2014). Prevalence of feeding disorders in children with cleft palate only: A retrospective study. Clinical Oral Investigations, 18(5), 1507–1515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-013-1117-x

Eddy, K. T., Thomas, J. J., Hastings, E., Edkins, K., Lamont, E., Nevins, C. M., Patterson, R. M., Murray, H. B., Bryant-Waugh, R., & Becker, A. E. (2015). Prevalence of DSM-5 avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric gastroenterology healthcare network. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(5), 464–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22350

Erkin, G., Culha, C., Ozel, S., & Kirbiyik, E. G. (2010). Feeding and gastrointestinal problems in children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 33(3), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283375e10

Fisher, M. M., Rosen, D. S., Ornstein, R. M., Mammel, K. A., Katzman, D. K., Rome, E. S., Callahan, S. T., Malizio, J., Kearney, S., & Walsh, B. T. (2014). Characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents: A “new disorder” in DSM-5. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 49–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.013

Francis, D. O., Krishnaswami, S., & McPheeters, M. (2015). Treatment of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding outcomes: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 135(6), e1458–e1466. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0658

Geyer, L. A., McGowan, J. S. (1995). Positioning infants and children for videofluroscopic swallowing function studies. Infants and Young Children, 8(2), 58-64.

Gisel, E. G. (1988). Chewing cycles in 2- to 8-year-old normal children: A developmental profile. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 42(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.42.1.40

Homer, E. (2008). Establishing a public school dysphagia program: A model for administration and service provision. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2008/018)

Huckabee, M. L., & Pelletier, C. A. (1999). Management of adult neurogenic dysphagia. Singular.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

Jaffal, H., Isaac, A., Johannsen, W., Campbell, S., & El-Hakim, H. G. (2020). The prevalence of swallowing dysfunction in children with laryngomalacia: A systematic review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 139, 110464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110464

Johnson, D. E., & Dole, K. (1999). International adoptions: Implications for early intervention. Infants & Young Children, 11(4), 34–45.

Le Révérend, B. J. D., Edelson, L. R., & Loret, C. (2014). Anatomical, functional, physiological and behavioural aspects of the development of mastication in early childhood. British Journal of Nutrition, 111(3), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513002699

Lefton-Greif, M. A. (2008). Pediatric dysphagia. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 19(4), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2008.05.007

Lefton-Greif, M. A., Carroll, J. L., & Loughlin, G. M. (2006). Long-term follow-up of oropharyngeal dysphagia in children without apparent risk factors. Pediatric Pulmonology, 41(11), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20488

Lefton-Greif, M. A., McGrattan, K. E., Carson, K. A., Pinto, J. M., Wright, J. M., & Martin-Harris, B. (2017). First steps towards development of an instrument for the reproducible quantification of oropharyngeal swallow physiology in bottle-fed children. Dysphagia, 33(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9834-y

Logemann, J. A. (1998). Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. Pro-Ed.

Logemann, J. A. (2000). Therapy for children with swallowing disorders in the educational setting. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461.3101.50

Mandich, M. B., Ritchie, S. K., & Mullett, M. (1996). Transition times to oral feeding in premature infants with and without apnea. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 25(9), 771–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb01493.x

Manikam, R., & Perman, J. A. (2000). Pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 30(1), 34–46.

McCain, G. C. (1997). Behavioral state activity during nipple feedings for preterm infants. Neonatal Network, 16(5), 43–47.

McComish, C., Brackett, K., Kelly, M., Hall, C., Wallace, S., & Powell, V. (2016). Interdisciplinary feeding team: A medical, motor, behavioral approach to complex pediatric feeding problems. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 41(4), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000252

Moreno-Villares, J. M. (2014). La transición a cuidado adulto para niños con desórdenes neurológicos crónicos: ¿Cual es la mejor manera de hacerlo? [Transition to adult care for children with chronic neurological disorders: Which is the best way to make it?]. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 29(Suppl. 2), 32–37.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2010). Number of all-listed diagnoses for sick newborn infants by sex and selected diagnostic categories [Data file]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/8newsborns/2010new8_numbersick.pdf [PDF]

Newman, L. A., Keckley, C., Petersen, M. C., & Hamner, A. (2001). Swallowing function and medical diagnoses in infants suspected of dysphagia. Pediatrics, 108(6), e106. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.6.e106

Norris, M. L., Spettigue, W. J., & Katzman, D. K. (2016). Update on eating disorders: Current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 213–218. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S82538

Pados, B. F., & Fuller, K. (2020). Establishing a foundation for optimal feeding outcomes in the NICU. Nursing for Women’s Health, 24(3), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2020.03.007

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, 29 U.S.C. § 701 et seq. https://www.ada.gov/regs2016/504_nprm.html

Reid, J., Kilpatrick, N., & Reilly, S. (2006). A prospective, longitudinal study of feeding skills in a cohort of babies with cleft conditions. The Cleft Palate–Craniofacial Journal, 43(6), 702–709. https://doi.org/10.1597/05-172

Rodriguez, N. A., & Caplan, M. S. (2015). Oropharyngeal administration of mother’s milk to prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in extremely low-birth-weight infants. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 29(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000082

Seiverling, L., Towle, P., Hendy, H. M., & Pantelides, J. (2018). Prevalence of feeding problems in young children with and without autism spectrum disorder: A chart review study. Journal of Early Intervention, 40(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815118789396

Shaker, C. S. (2013a). Cue-based feeding in the NICU: Using the infant’s communication as a guide. Neonatal Network, 32(6), 404–408. https://doi.org/10.1891/0730-0832.32.6.404

Shaker, C. S. (2013b, February 1). Reading the feeding. The ASHA Leader, 18(2), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FTRI.18022013.42